Over the course of my career I have consistently seen security in the approval chain for various IT operations and business requests, such as identity, network and even customer contracts. Having security in the approval chain may seem logical at first glance, but it can actually mask or exacerbate underlying operations issues. Having a second set of eyes on requests can make sense to provide assurance, but the question is – does it make sense for security to be an approver?

Understand The Scope of Your Security Program

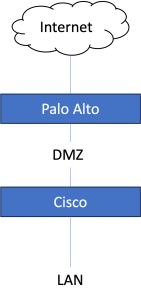

First and foremost, the scope of your security program will ultimately dictate how and when security should be included in an approval process. For example, if security owns networking or identity, then it will make sense to staff an operations team to support these areas and it will make sense to have security as an approver for requests related to these functions.

It may also make sense to include security in the approval chain as an evaluator of risk for functions security doesn’t own. For example, security won’t own the overall contract, finance or procurement processes, but they should be included as an approver to make sure contract terms and purchases align to security policies and are not opening up the business to unnecessary risk. They can also be included in large financial transfers as a second set of eyes to make sure the business isn’t being scammed out of money. In these examples, security is creating good friction to slow critical processes down in a healthy way to make sure they make sense and to use time as a defense mechanism.

Other Benefits Of Security As An Approver

Including security as an approver for general IT processes can have other benefits, but these need to be weighed carefully against the risks and overall function of the business. For example, security can help provide an audit trail for approving activities that may create risk for the company. This audit trail can be useful during incident investigations to determine root cause for an incident. It can also help avoid compliance gaps for things like FedRAMP, SOC, etc. where some overall business or IT changes need to be closely managed to maintain compliance. However, creating an audit trail is not unique to the security function and, if the process is properly designed, can be performed by other functions as well.

Another advantage of including security in the approval chain is separation of duties. For example, if one team owns identity, and they are requesting elevated privileges to something, it can present a conflict of interest if they approve their own access requests. Instead, security often acts as a secondary reviewer and approver to provide separation of duties to make sure requests by a team that owns the thing isn’t approving their own requests.

Where Including Security As An Approver Can Go Wrong

The biggest issue with having security in the approval chain for most things is they typically are not the owner of those things. If approval processes are not designed properly (with other approvers besides security), then the processes can confuse ownership and give a false impression of security or compliance. For example, I typically see security as an approver for identity and access requests when security doesn’t own the identity function. At first glance, this seems to make sense because identity is a critical IT function that needs to be protected. However, if security doesn’t own the identity function (or the systems that need access approved), how do they know whether the request should be approved or not. Instead, what happens is almost all requests end up being approved (unless they are egregious) and the process serves no real purpose other than creating unnecessary friction and giving a false sense of security.

Another issue I have seen with including security in the approval chain is they effectively become “human software” where they are manually performing tasks that should be automated instead. Using security personnel as “middleware” masks the true pain and inefficiency of the process for the process owner. This takes critical human capital away from their intended purpose, is a costly solution to a problem and opens up the business to additional risk.

When Does It Make Sense For Security To Be An Approver?

I’ve listed a few examples where it makes sense for security to be an approver for things it doesn’t own – like large financial transactions, some procurement activities and security specific contract terms. However, I argue security shouldn’t be included as an approver in most IT operations processes unless security actually owns that process or thing that needs a specific security approval. Instead, the business owner of the thing should be the ultimate approver and processes should be designed to provide appropriate auditing and compliance, but without needing security personnel to perform those checks manually.

One of the few areas where it will always make sense to have security as an approver is for security exceptions. First, exceptions should be truly exceptional and not used as a band-aid for broken or poorly designed process. Second, exceptions should be grounded in business risk, while documenting the evaluation criteria, decisions, associated policies and duration. This is a core security activity because exceptions are ultimately evaluating risk and deviation from policy. I’ve written other posts about how the exception process can have other benefits as well.

Wrapping Up

Don’t fall into the trap of using your security team as a reviewer and approver for IT operations requests if security doesn’t actually own the thing related to the request. This places the security team in an adversarial position, can be a costly waste of resources, masks process inefficiencies, gives a false sense of security and can open up the business to risk. Instead, be ruthlessly focused in how your security team is utilized to make sure when they are engaged it is to perform a function that is at the core of their mission – protecting the business and managing risk.