Late one Friday afternoon a call comes in and you find out you landed your next CISO role. All the interview prep, research, networking and public speaking has paid off! Then it dawns on you that you could be walking into a very difficult situation over the next few months. Even though the interview answered a lot of questions, you won’t know the reality of the situation until you start. How will your expectations differ from reality? What can you do to minimize risk as you come up to speed? How should you navigate these first 90-180 days in your new role?

Prior To Starting

Let’s assume you have some time to wind down your current position and you are also going to take some time off before starting the new role. During this transition period I highly advise you reach out to your peers in the new role and start asking questions to get more detail about the top challenges and risks you need to address. Start with the rest of the C-Suite, but also get time with board members and other senior business leaders to get their perspectives. Focus on building rapport, but also gather information to build on what you learned during the interview process so you can hit the ground running.

You can also use this time to reach out to your CISO peers in your network who are in the same industry, vertical or company type to get their perspective on what they did when they first joined their company. Learn from their experience and try to accelerate your journey once you start. Keep the lines of communication open so if you run into a situation you are unsure of you can ask for advice.

Once You Start

Build Relationships

First and foremost, start building relationships as quickly as possible. Target senior leadership first, such as board members, the C-Suite and other senior leaders. Work your way down by identifying key influencers and decision makers throughout the org. Play the “new person card” and ask questions about anything and everything. Gain an understanding of the “operational tempo” of the business such as when key meetings take place (like board meetings). Understand the historical reasons why certain challenges exist. Understand the political reasons why challenges persist. Understand the OKRs, KPIs and other business objectives carried by your peers. Learn the near and long term strategy for the business. Start building out a picture of what the true situation is and how you want to begin prioritizing.

Understand the historical reasons why certain challenges exist. Understand the political reasons why challenges persist.

Plan For The Worst

Don’t be surprised if you take a new role and are immediately thrown into an incident or other significant situation. You may not have had time to review playbooks or processes, but you can still fall back on your prior experience to guide the team through this event and learn from it. Most importantly, you can use this experience to identify key talent and let them lead, while you observe and take notes. You can also use your observation of the incident to take notes on things that need to be improved such as interaction with non-security groups, when to inform the board, how to communicate with customers or how to improve coordination among your team.

Act With Urgency

Your first few months in the role are extremely vulnerable periods for both you and the company. During this period you won’t have a full picture of the risks to the business and you may not have fully developed your long term plan. Despite these challenges, you still need to act with urgency to gain an understanding of the business and the risk landscape as quickly as possible. Build on the existing program (if any) to document your assumptions, discoveries, controls and risks so you can begin to litigation proof your org. Map the maturity of security controls to an industry framework to help inform your view of the current state of risk at the company. Begin building out templates for communicating your findings, asks, etc. to both the board and your peers. Most importantly, the company will benefit from your fresh perspective so be candid about your findings and initial recommendations.

Evaluate The Security Org

In addition to the recommendations above, one of the first things I like to do is evaluate the org I have inherited. I try to talk to everyone and answer a few questions:

- Is the current org structure best positioned to support the rest of the business?

- How does the rest of the business perceive the security org?

- Where do we have talent gaps in the org?

- What improvements do we need to make to culture, diversity, processes, etc. to optimize the existing talent of the org?

Answering these questions may require you to work with your HR business partner to build out new role definitions and career paths for your org. You may also need to start a diversity campaign or a culture improvement campaign within the security org. Most importantly, evaluate the people in your org to see if you have the right people in the right places with the right skillsets.

A Plan Takes Shape

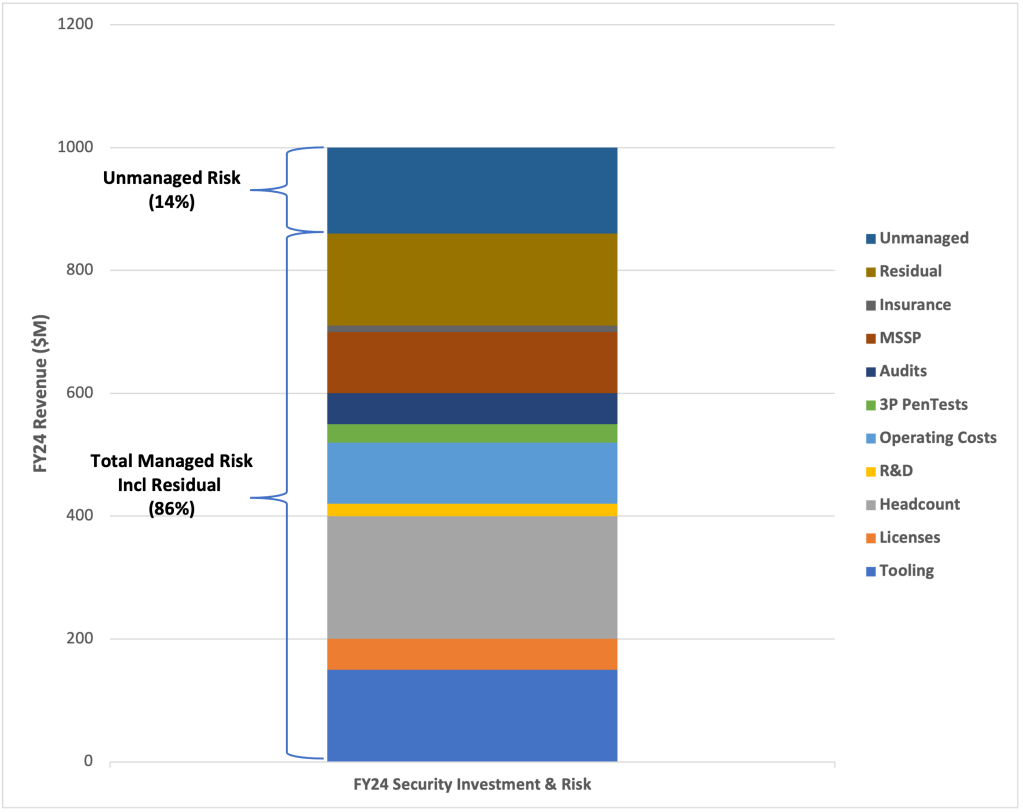

As you glide past the 90 day mark and start establishing your position as a trusted business partner, you should arrive at a point where a clear vision and strategy is starting to take shape. Use the information you have gathered from your peers, your program documentation and your observations to start building a comprehensive plan and strategy. I’ve documented this process in detail here. In addition to building your program plan you can also begin to more accurately communicate the state of your security program to senior leaders and the board. Show how much the existing program addresses business risk and where additional investment is needed. I’ve documented a suggested process here. Somewhere between your 90 and 180 day mark you should have a formalized plan for where you are over invested, under invested or need to make changes to optimize existing investment. This could include restructuring your org, buying a new technology, adjusting contractual terms or purchasing short term cyber insurance. It could even include outsourcing key functions of the security org for the short term, until you can get the rest of your program up to a certain standard. Most importantly, document how you arrived at key decisions and priorities.

Take Care Of Yourself

Lastly, on a personal note, make sure to take care of yourself. Starting a new role is hectic and exciting, but it is also a time where you can quickly overwork yourself. Remember building and leading a successful security program is a marathon not a sprint. The work is never done. Get your program to a comfortable position as quickly as possible by addressing key gaps so you can avoid burning yourself out. Try to establish a routine to allow for physical and mental health and communicate your goals to your business partners so they can support you.

During this time (or the first year) you may also want to minimize external commitments like dinners, conferences and speaking engagements. When you start a new role everyone will want your time and attention, but be cautious and protective of your time. While it is nice to get a free meal, these dinners can often take up a lot of time for little value on your end (you are the product after all). Most companies have an active marketing department that will ask you to engage with customers and the industry. Build a good relationship with your marketing peers to interweave customer commitments with industry events so you are appropriately balancing your time and attending the events that will be most impactful for the company, your network and your career.

Wrapping Up

Landing your next CISO role is exciting and definitely worth celebrating. However, the first 90-180 days are critical to gain an understanding of the business, key stakeholders and how you want to start prioritizing activities. Most importantly, build relationships, act with urgency and document everything so you can minimize the window of exposure as you are coming up to speed in your new role.