There are a lot of different ways for CISOs to think about and measure risk, which can be bucketed into two different categories. Qualitative measurement, which is a subjective measurement that follows an objective process or quantitative measurement, which is an objective measurement grounded in dollar amounts. Quantitative risk measurement is what CISOs should strive to achieve for a few reasons. One, it grounds the risk measurement in objective numbers which removes people’s opinions from the calculation; two, it assesses risk in terms of dollar amounts, which is useful for communicating to the rest of the business; and three, it can highlight areas of immaturity across the business if they are unable to quantify how their division contributes to the overall bottom line of the company. In this post I want to explore how CISOs should think about quantitatively measuring risk and in particular, measuring mitigated, unmitigated and residual risk for the business.

Where should you start?

A good place to start is with an industry standard risk management framework like NIST 800-37, CIS RAM or ISO 31000 and for the purposes of this post I’ll stick with the NIST 800-37 to be consistent. In order for CISOs to obtain a qualitative risk assessment from the NIST 800-37 they need to add a step into the categorize step by working with finance and the business owners to understand the P&L of the system(s) they are categorizing. The first step is to go through every business system and get a dollar amount (in terms of revenue) for how much the systems(s) contribute to the overall bottom line of the business.

Internal and External Security Costs

After you get a revenue dollar amount for every set of systems, you now need to move to the assess stage of the NIST 800-37 RMF to determine which security controls are in place to protect the systems, how much they cost and ultimately what percentage the security controls cover. There are two categories of security controls and costs you will need to build a model for. The first category is internal costs, which includes:

- Tooling and technology

- Licenses

- Training

- Headcount (fully burdened cost)

- Travel

- R&D

- Technology operating costs (like cloud costs directly attributable to security tooling, etc.)

The second category is external costs, which includes:

- 3rd party penetration tests

- Audits

- Managed Security Service Provider (MSSP) costs

- Insurance

As you fill in the costs or annual budget for each of these items you can map the coverage of these internal and external costs to your business to determine the total cost of your security program and how much risk the program is able to cover (in terms of a percentage).

Mapping Risk Coverage

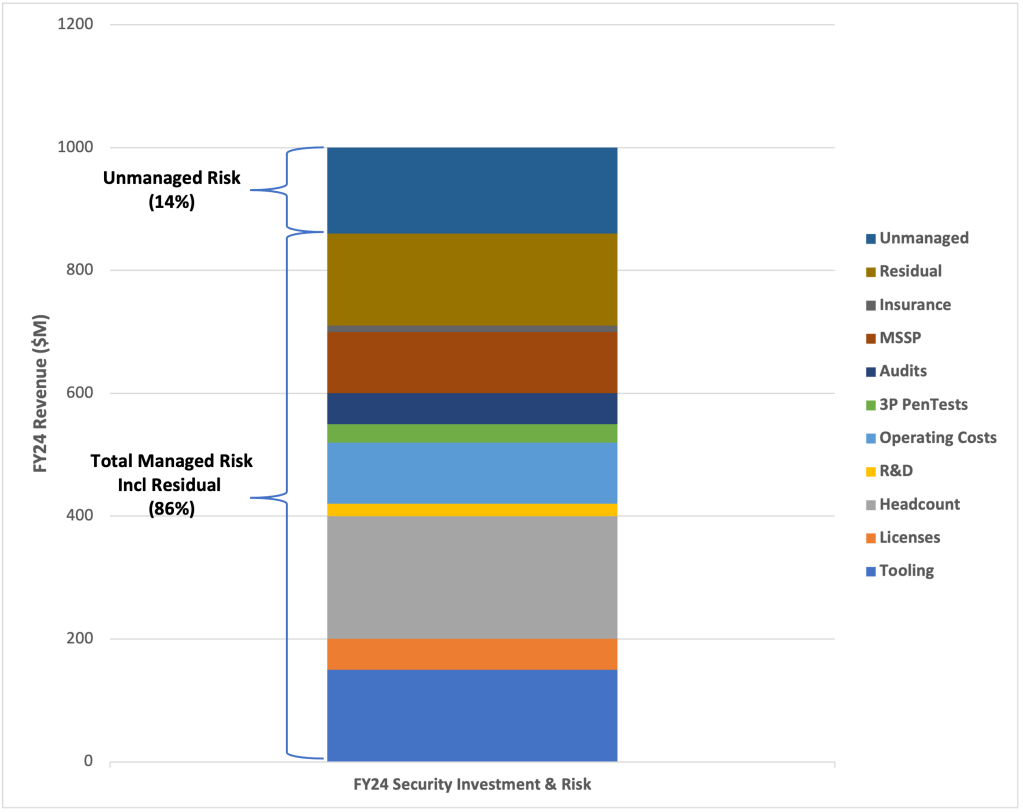

Once you have all of these figures you can start to map risk coverage to determine if your security program is effectively protecting the business. Let’s say your business generates $1B in annual revenue. Your goal as a CISO is to maintain a security program that provides $1B of risk coverage of the business. Or, if you are unable to provide total coverage, then you need to communicate which parts of the business are not protected so the rest of the C-Suite and board can either accept the risk or approve additional funding.

As a simple example, let’s say you spend $1M/year on a SIEM tool, which takes 6 people to operate and maintain. The total cost of the 6 people is approximately $6M / yr (including benefits, etc.). The SIEM and people provide 100% monitoring coverage for the business and the SIEM and people can be mapped to 20% of your security controls in NIST. I’m skipping a lot of details for simplicity, but for a $1B business this means your SIEM function costs $7M / yr, but protects $200M of revenue ($1B x 20%). As you map the other tools, processes, people, etc. back to the business you will get a complete picture of how much risk your security program is managing and make informed decisions about your program to the board.

For example, you may find your security program costs $100M / year, but is only able to manage risk for $750M (75%) of the business. Your analysis should clearly articulate whether this remaining 20% of risk is residual (will never go away and is acceptable) or is unmanaged and needs attention.

Complete The Picture

By mapping your security program costs to the percentage of controls they cover and then mapping those controls to the business, CISOs should be able to get an accurate picture of the effectiveness of their security program. By breaking out the security program costs into the internal and external categories I’ve listed above, they can also compare and contrast the costs to the total amount of risk to determine which investments yield the best value. These analyses can be extremely effective when having conversations with the rest of the C-Suite or board, who may be inclined to decline additional budget requests or subjectively recommend a solution. By informing these stakeholders of the cost per control and the risk value of that cost, you can help them support your recommendation for additional investment to help increase risk management coverage or to help increase the value of risk management provided by the security program.

The following chart is an example of what this analysis can yield.

Once you have this data and analysis you can start driving conversations with the rest of the C-Suite and the board to inform them of how much risk is being managed, how much is residual, how much risk is unmanaged and your recommendation for additional investment (or acceptance). These conversations can also benefit from further analysis such as the ratio of cost to managed risk to determine which investment is providing the best value and ultimately support your recommendation for how the company should manage this risk going forward (people or technology).

Wrapping Up

Managing P&L is a fundamental skill for all CISOs to master and can help drive conversations across the company for how risk is being managed. CISOs need to master skills in financial analysis and partner with other parts of the business like business operations or business owners to understand how the business operates and what percentage of the business is effectively covered by the existing security program. The results of this analysis will help CISOs shape the conversation around risk, investment and ultimately the strategic direction of the business.