We have all been there…we’ve had moments in our life where we have had to “comply” or “just do it” to meet a security requirement that doesn’t make sense. We see this throughout our lives when we travel, in our communities and in our every day jobs. While some people may think security theater has merit because it “checks a box” or provides a deterrent, in my opinion security theater does more harm than good and should be eradicated from security programs.

What Is Security Theater?

Security theater was first coined by Bruce Schneier and refers to the practice of implementing security measures in the form of people, processes or technologies that give the illusion of improved security. In practical terms, this means there is something happening, but what that something is and how it actually provides any protection is questionable at best.

Examples Of Security Theater

Real life examples of security theater can be seen all over the place, particularly when we travel. The biggest travel security theater is related to liquids. TSA has a requirement that you can’t bring liquids through security unless they are 3 ounces or smaller. However, you can bring a bottle of water through if it is fully frozen…what? Why does being frozen matter? What happens if I bring 100, 3 ounce shampoo bottles through security? I still end up with the same volume of liquid and security has done nothing to prevent me from bringing the liquid through. As for water, the only thing that makes sense for why they haven’t relaxed this requirements is to prop up the businesses in the terminal that want to sell overpriced bottles of water to passengers. Complete theater.

“Security theater is the practice of implementing security measures that give the illusion of improved security.”

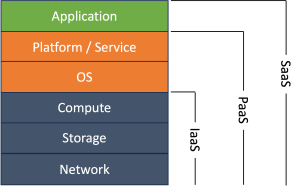

Corporate security programs also have examples of security theater. This can come up if you have an auditor that is evaluating your security program against an audit requirement and they don’t understand the purpose of the requirement. For example, and auditor may insist you install antivirus on your systems to prevent viruses and malware, when your business model is to provide Software as a Service (SaaS). With SaaS your users are consuming software in a way that nothing is installed on their end user workstations and so there is little to no risk of malware spreading from your SaaS product to their workstations. Complete theater.

Another example of security theater is asking for attestation a team is meeting a security requirement instead of designing a process or security control that actually achieves the desired outcome. In this example, the attestation is nothing more than a facade designed to pass accountability from the security team, that should be designing and implementing effective controls, to the business team. It is masking ineffective process and technologies. Complete theater.

Lastly, a classic example of security theater is security by obscurity. Otherwise known as hiding in plain sight. If your security program is relying on the hope that attackers won’t find something in your environment then prepare to be disappointed. Reconnaissance tools are highly effective and with enough time threat actors will find anything you are trying to hide. Hope is not a strategy. Complete theater.

What Is The Impact Of Security Theater?

Tangible And Intangible Costs

Everything we do in life has a cost and this is certainly true with security theater. In the examples above there is a real cost in terms of time and money. People who travel are advised to get to the airport at least two hours early. This cost results in lost productivity, lost time with family and decreased self care.

In addition to tangible costs like those above, there are also intangible costs. If people don’t understand the “why” for your security control, they won’t be philosophically aligned to support it. The end result is security theater will erode confidence and trust in your organization, which will undermine your authority. This is never a place you want to be as a CISO.

Some people may argue that security theater is a deterrent because the show of doing “security things” will deter bad people from doing bad things. This sounds more like a hope than reality. People are smart. They understand when things make sense and if you are implementing controls that don’t make sense they will find ways around them or worse, ignore you when something important comes up.

With any effective security program the cost of a security control should never outweigh the cost of the risk, but security theater does exactly that.

Real Risks

The biggest problem with security theater is it can give a false sense of security to the organization that implements it. The mere act of doing “all the things” can make the security team think they are mitigating a risk when in reality they are creating the perfect scenario for a false negative.

How To Avoid Security Theater?

The easiest way to avoid security theater is to have security controls that are grounded in sound requirements and establish metrics to evaluate their effectiveness. Part of your evaluation should evaluate the cost of the control versus the cost of the risk. If your control costs more than the risk then it doesn’t make sense and you shouldn’t do it.

The other way to avoid security theater is to exercise integrity. Don’t just “check the box” and don’t ask the business you support to check the box either. Take the time to understand requirements from laws, regulations and auditors to determine what the real risk is. Figure out what an effective control will be to manage that risk and document your reasoning and decision.

The biggest way to avoid security theater is to explain the “why” behind a particular security control. If you can’t link it back to a risk or business objective and explain it in a way people will understand then it is security theater.

Can we stop with all the theater?