Almost weekly I see someone post a question on social media asking: “Is renewing my security certification worth it?” This is a valid question since security certifications are often expensive, time consuming and hard won. Maintaining your security certification may be required to land a new job, but not required to continue in the role. At the end of the day the question people are really asking is: “Is the continued expense of this certification worth it after I’ve landed the role I’m after or achieved my career objectives?” In this post I’ll explore the pros and cons of renewing a security certification and wrap up with my specific recommendation for those of you looking for guidance.

Getting Certifications

There are a number of popular security certifications that can demonstrate general or specific expertise. Some of the most popular are:

- CISSP

- CISM

- CEH

- Security+

- CISA

- CCSP

Along with the variety of certifications there are different ways to earn a certification. The least expensive and most time consuming is to purchase the course material, self study and then sit for the exam. The most expensive and least time consuming is to attend a boot camp and then test for the exam on the last day. If you are lucky your employer will pay for or reimburse the expense of the certification. No matter which way you go, there is a material cost in terms of dollars and time. This cost can make people reluctant to let certifications expire because the certifications have a high barrier to entry, but a (relatively) low maintenance cost.

Pros To Renewing

One of the main reasons to continue to maintain your certification is because they are required by some job roles in order to be hired and perform the role. One example of this is in the U.S. Government Department of Defense (DoD) 8570 Approved Baseline Certifications. The 8570 specifies “Personnel performing IA functions must obtain one of the certifications required for their position, category/specialty and level to fulfill the IA baseline certification requirement.” So if you want the job, and want to keep the job, then you need the certification.

In addition to job requirements, maintaining an active certification gives the impression of having expertise in a particular area. Demonstrating expertise is useful when speaking, consulting, providing legal testimony or simply cementing your position as an expert in the field of security. Expertise is useful when trying to land a new role or get a promotion. This can also be useful to limit personal liability if you can demonstrate you followed the best practices indicated by the certification. Maintaining a certification and this expertise is arguably a low cost, low effort activity with a lot of upside and not a lot of downside. Even though there is a dollar cost for renewal, this is a minor amount compared to the overall expense or time invested in getting the certification in the first place.

One final reason to maintain your security certifications is because it demonstrates you have a baseline level of knowledge as indicated by the certification. When you were studying and testing for the certification you were learning new concepts and confirming mastery of other concepts. This can be useful to validate your expertise, but also to demonstrate to others that you have mastered these concepts and can operate at the same level as other individuals that have the certification. This goes beyond demonstrating expertise in that is establishes a baseline of knowledge for security practitioners in the field and this is why employers often list specific certifications on job descriptions.

Cons To Renewing

Even though there are a number of benefits to maintaining a certification, there are also a lot of cons.

First, there is the obvious annual cost for renewing the certification. Not only is there a dollar cost, but there is also usually a time cost in the form of continuing education credits that have to be earned and submitted throughout the year. The idea is to drive engagement in the security community by requiring these continuing education credits, but in my opinion this has had mixed results. For anyone on the fence about renewing a certification the time and dollar cost can be the breaking point where it no longer makes sense to continue to invest in something that isn’t demonstrating continued value.

Speaking of continued value, what are you really getting by spending time on continuing education and paying the renewal fee? You get the privilege to list the certification on your resume, but you’ve already gained the knowledge and passed the test. Renewing doesn’t typically require another test so is there really continued value (assuming you aren’t required to maintain it for your job)? The value is questionable if it isn’t required and so it can be difficult to justify maintaining.

Another downside to maintaining the certification is the continuing education credits. There are a number of low cost or free ways to earn credits, but it can be difficult or almost impossible to get to the required number without spending money. This is a con in my opinion because renewing the certification is perpetuating additional expenses such as more certifications, attending more conferences or other expenses just to earn enough credits. This means even though there is a low renewal cost, there can be a really high dollar or time cost to earn enough continuing education credits to maintain the certification.

In the pros section I listed the DoD 8750, which requires certain certifications to obtain and perform certain roles. However, requiring certifications for a job can also have a downside by eroding the exclusivity of the certification. This happened to the MCSE in the late 90’s and early 2000’s when everyone wanted an MCSE because it paid really well. However, soon everyone had it even if they weren’t doing the job and the MCSE became useless. It was no longer a good barometer for demonstrating expertise because so many non experts had it. Some security certifications are the same way and the DoD 8570 (or other employers) can contribute to this erosion of exclusivity if the people earning the certification are simply getting it to fill the role instead of becoming experts in the field.

One last con for renewing certifications is you may no longer be doing the type of job that requires the certification. In the past I held the GCIH, GREM and GPEN certifications, but I no longer do those hands on activities so it doesn’t make sense for me to maintain those certifications. If your career has taken you on a different path, then you no longer need to maintain the cert. Also, I will argue your job title can be more useful to demonstrate expertise than a certification. This isn’t always the case and this can sometimes be difficult to tease out with discretionary titles, but generally if you have carried the CISO or CSO title in some capacity do you really need to maintain an active certification? I’ve seen several individuals list their expired certifications on their resume, which continues to demonstrate the expertise, but without the added expense.

My Recommendation

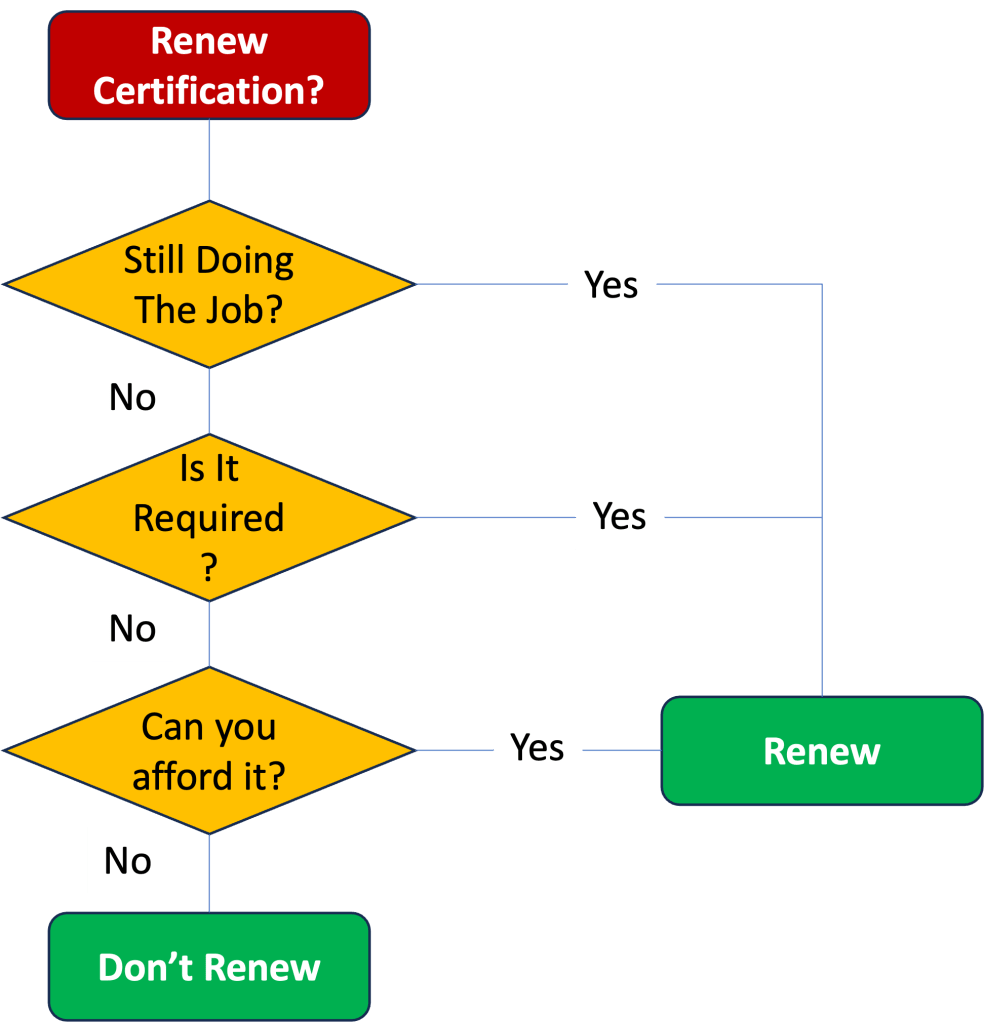

If you are on the fence about whether or not to renew your security certification here is a simplistic flow chart for helping you with the decision. Feel free to recreate and add your own additional criteria as necessary.

My particular recommendation is as follows: if you want to maintain the credibility, demonstrate expertise, are still doing the job and can afford the renewal cost (both time and dollar), then renewing is typically not too expensive and worth it. I am also seeing a lot of job descriptions require active certifications so if you are about to job hunt or at risk of getting laid off then maintaining your certifications is a good idea. If you are no long doing the job, don’t need the credibility or expertise and the certification isn’t required by your job then I suggest no longer renewing and focusing on other areas. In my case, I have dropped most of the specialist certifications, while maintaining the generalist certifications in line with my role.